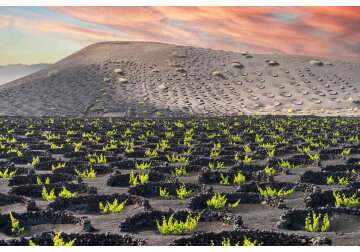

The ingenious wines birthed from black volcanic craters

In Spain's Lanzarote Island, conical hollows built into layers of volcanic ash yield wines that have been created from generations of ingenuity and hard work.

When viewed from a distance, the vineyards of Spain's Lanzarote island show few signs of life. The sweeping jet-black terrain is pitted with a series of conical hollows, like the thumbprints of a mythical giant pressed into the dark earth. But get a little closer, and each crater reveals a vine at its heart.

Just 127km from Africa, Lanzarote is the easternmost of the Canary Islands, an archipelago shaped by fire. Even among its combustible neighbours, it stands out, bearing the moniker "Volcano Island" for its more than 300 lava spewers. While the landscape is often described as lunar, it also conjures thoughts of what Earth might have looked like before the advent of humanity.

The volcanoes of Timanfaya National Park last flared in 1824, but it was the previous series of eruptions – starting in 1730 and lasting six years – that transformed life on this island. Lava blanketed a quarter of the area, destroying villages, causing famine and prompting many to emigrate. The calamity's parting gift was a thick layer of picón (volcanic ash).

Wine has been produced in the archipelago since the 15th Century, when Spanish colonists first arrived. The island of Tenerife found eager customers in England – but unlike Tenerife, Lanzarote's residents made wine only for personal consumption, until the 1730 eruptions.

For the hardy few that stayed after the disaster, however, necessity became the mother of invention. After digging through the picón by hand, in search of the arable land that used to produce cereal grains, they found that their soil was no longer suited to those crops. Grapevines, however, could survive and even thrive, and the secret ingredient was the dreaded ash itself.

Most of the world's wine regions rely on at least 300mm of annual rainfall, but Lanzarote receives only about 150mm, and frequently less. Adding insult to injury, the island is routinely buffeted by intense trade winds from the northeast and must also contend with the calima, dust storms that kick up several times a year, sometimes lasting for days. Sand and soil from the Sahara get suspended in the hot, dry air, turning the sky an otherworldly sepia hue, and veiling the island with thick haze. When a calima rolls in, locals joke that someone must be playing soccer in Morocco.

Under these circumstances, farmers had no choice but to get creative. "From one day to the next, their fields were buried in ash, and everything they knew how to do had disappeared," says Nereida Pérez, the technical coordinator of Lanzarote wines' regulatory council. Their solution? Dig hoyos, or conical hollows, three meters wide by three to four meters deep. After planting their grapevines, they covered them with a thick layer of picón and girded the north-eastern side of each hoyo with a low semi-circular wall, built from lava stones.

It was clever engineering. The cone's shape collects the sparse rain and dew, and funnels the water to the plant's roots, while the picón draws moisture from the air and retains it in the soil, regulating its temperature. The walls shield the vines from the winds and protect the hoyos' pitched slopes from erosion and collapse, preventing the ash from smothering the vines' roots.

And that's how a wine region rose from the ashes, literally. "Those folks were visionaries. They had the capacity to adapt," says Elisa Ludeña, the young winemaker and technical director of El Grifo. Established in 1775, El Grifo is the oldest winery in the Canaries and one of the 10 oldest in Spain. It's also one of 28 currently active wineries on an island half the size of Oahu.

The grape that predominates is Malvasía Volcánica, a white variety found only in the archipelago and grown primarily on Lanzarote, accounting for 60% of the island's production. The remainder is largely a combination of the white varieties Listán Blanco, Vijariego Blanco and Moscatel de Alejandría, and the red Listán Negro and Syrah. Some vines are nearly 200 years old, thanks to vineyards that were never infested with phylloxera – an insect that decimated many European wineries in the 1800s, forcing producers to graft their plants onto the rootstock of American vines, which proved more resistant.

Given Lanzarote's location, just on the edge of the 30th parallel north, it might seem a fool's errand to try to produce quality wines, but the primordial landscape and persistent winds actually help, controlling temperatures and keeping pests at bay. "Phylloxera is not at home in sandy soils, and most volcanic soil is ash," says award-winning sommelier Josep Roca of El Celler de Can Roca in Girona, Spain.

bbc.com