An obsessed insect hunter: The creepy-crawly origins of daylight savings

An early proponent of daylight savings pushed for the time-shift so he'd have more time to hunt insects. Meet some of the bugs whose names he inspired and stories he helped tell.

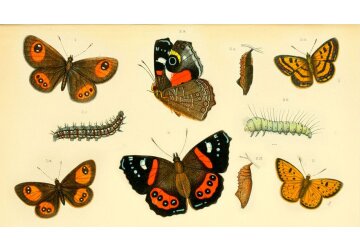

In the early 1880s, an adolescent George Hudson was already enamoured by insects. At the age of 13, the budding amateur naturalist wrote his first manuscript – based on insects he collected and drew in meticulous detail. By the time of his death in 1946, he had penned and illustrated seven books, and amassed one of the largest collections of insect specimens in New Zealand.

But this prolific commitment to invertebrates – especially moths and butterflies – was not without its obstacles. For as the bug-loving teenager entered the workforce as a postal clerk, he came up against a problem: there were more insects out there than he had available daylight hours in which to hunt them.

Not one to let his insect-studying instincts be curtailed, however, Hudson proposed a solution: shift the clocks back two hours during summer months – a concept which foreshadows the modern system of daylight saving time.

Such a shift, he argued in front of the Wellington Philosophical Society in 1895 and 1898, would make use of early morning daylight for work and open up "a long period of daylight leisure" in the evening "for cricket, gardening, cycling or any other outdoor pursuit desired". As well as saving on the use of artificial light, the switch would especially benefit "the numerous classes who are obliged to work indoors all day, and who, under existing arrangements, get a minimum of fresh air and sunshine", he suggested.

At first, his proposition was met with ridicule and, although it gained ground and support in the subsequent years, it didn't progress much further at the time. But he was also not the only person of his era making such a case.

In the UK, the builder William Willet noticed that during his early morning horse-ride to work, the shutters remained drawn in workers' cottages. By moving back summertime hours, he, like Hudson, reasoned that people could start their day earlier and have more time for leisure after work.

Willet's original proposal involved changing the clocks by 20 minutes each Sunday in April, and back over four Sundays by 20 minutes in September, explains Emily Akkermans, Curator of Time at the Royal Observatory Greenwich. A single one hour change was ultimately settled on by his supporters and first presented before parliament in 1908 – yet it wasn't until 1916 that the wartime need to conserve fuel saw the measure officially adopted by Germany, and then finally, a few weeks later, by the UK.

Numerous other nations soon followed suit, including the US in 1918. And while Willet didn't survive to see the adoption of his cause, dying of influenza before the end of war, Hudson lived to see New Zealand pass a one hour shift into law in 1927.

In the meantime, Hudson had also kept himself busy. By arranging his work shifts so that he could use daylight hours to catch and paint bugs, he pursued his passion for entomology with rare intensity.

Not all the insects documented by Hudson exist today, however. A giant and enigmatic micromoth mentioned in his 1928 work, Titanomis sisyrota, may now be extinct, says Lees.

In ways like these, regardless of the changing attitudes to the Daylight Savings he helped usher in, Hudson has left his mark on the passage of time – and reminded us how it cannot be held still.

Bbc.com