2023 confirmed as world's hottest year on record

The year 2023 has been confirmed as the warmest on record, driven by human-caused climate change and boosted by the natural El Niño weather event.

Last year was about 1.48C warmer than the long-term average before humans started burning large amounts of fossil fuels, the EU's climate service says.

Almost every day since July has seen a new global air temperature high for the time of year, BBC analysis shows.

Sea surface temperatures have also smashed previous highs.

The Met Office reported last week that the UK experienced its second warmest year on record in 2023.

These global records are bringing the world closer to breaching key international climate targets.

"What struck me was not just that [2023] was record-breaking, but the amount by which it broke previous records," notes Andrew Dessler, a professor of atmospheric science at Texas A&M University.

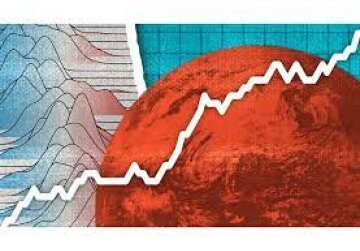

The margin of some of these records - which you can see on the chart below - is "really astonishing", Prof Dessler says, considering they are averages across the whole world.

An exceptional spell of warmth

It's well-known that the world is much warmer now than 100 years ago, as humans keep releasing record amounts of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

But 12 months ago, no major science body actually predicted 2023 being the hottest year on record, because of the complicated way in which the Earth's climate behaves.

During the first few months of the year, only a small number of days broke air temperature records.

But the world then went on a remarkable, almost unbroken streak of daily records in the second half of 2023.

Look at the calendar chart below, where each block represents a day in 2023. Records were broken on the days coloured in the darkest shade of red. From June, we're looking at a new record most days.

"2023 was an exceptional year, with climate records tumbling like dominoes," concludes Dr Samantha Burgess, Deputy Director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

This latest warning comes shortly after the COP28 climate summit, where countries agreed for the first time on the need to tackle the main cause of rising temperatures - fossil fuels.

While the language of the deal was weaker than many wanted - with no obligation for countries to act - it's hoped that it will help to build on some recent encouraging progress in areas like renewable power and electric vehicles.

This can still make a crucial difference to limit the consequences of climate change, researchers say, even though the 1.5C target looks likely to be missed.

"Even if we end up at 1.6C instead, it will be so much better than giving up and ending up close to 3C, which is where current policies would bring us," says Dr Friederike Otto, a senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London.

"Every tenth of a degree matters."

Bbc.com